As the world shifts away from fossil fuels to combat climate change, it is crucial to rapidly increase fossil-free electricity production while also avoiding harm to ecosystems. But can power production actually improve conditions for wildlife? When it comes to offshore wind and marine life, that seems to be the case.

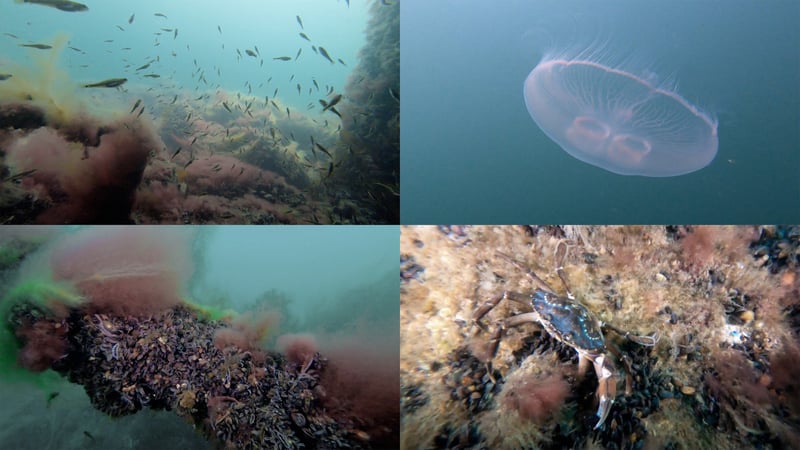

Marine life at Lillgrund wind farm. Photo: SCSC – Swedish Coast and Sea Center.

Sweden’s largest offshore wind farm Lillgrund, operated by Vattenfall, is situated in the Øresund sound between southern Sweden and Denmark, 10 km off the Swedish coast. When it was commissioned in 2007 it was the world’s third-largest wind farm.

The 48 turbines are surrounded by scour protections made of excavated rock with a 50 to 100 cm diameter extending approximately 20 meters out from each foundation. Those piles of rock and the foundations attract a variety of marine life.

“It is a beautiful area,” says Kjell Andersson.

Life attracts life

He is a diver, a marine environmental inspector, and deputy chairman of the Swedish Coast and Sea Center (SCSC), an independent non-profit organisation working to increase awareness and engagement for coastal and maritime issues. He has dived on Lillgrund on several occasions.

“When you build the wind turbines, artificial reefs are created. A large amount of mussels grow there, establishing themselves really quickly. You get a lot of small fish that finds shelter between the rocks. And when you get that, you attract a lot of other marine life. Brown seaweed such as laminaria also thrive, which is very positive,” Andersson says.

“I don’t see any negative effects from the wind turbines on Lillgrund, I only see them as positive,” he says.

The absence of fishing practices such as trawling also helps promote marine life at offshore wind farms.

The Lillgrund wind farm is unique in the sense that it has been monitored in a collaboration between Vattenfall and the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet, SLU) since before it was built, and a new study has just started and will be finished in 2027.

An earlier study of the wind farm, published in 2013, showed that a reef effect occurred and that some species of fish, such as cod and eel, were drawn to the turbines. No species avoided them. While that study found no evidence that the total amount of fish within the wind farm was increasing or decreasing, it pointed to a potential general increase in fish abundance over a longer time scale.

When these long-term studies are now conducted, Lena Bergström, a marine ecologist and associate professor at SLU, who has been working with both the 2013 study and this new study, says she hopes the ongoing study will show that to be the case.

“When a reef effect occurs, species accumulate near the foundations of the wind turbines. Over time, it can lead to an increase in primary producers such as algae, and benthic animals, which serve as essential food for fish, making the area more productive. The theory suggests that this could ultimately boost the overall fish population,” Bergström says.

Water replenishment holes adapted for marine life

Tim Wilms, a bioscience expert and marine ecologist at Vattenfall, says some modern wind farms can be expected to be even more attractive to wildlife. In September last year, the company inaugurated the Hollandse Kust Zuid wind farm in the North Sea, 18–36 kilometres off the Dutch coast together with partners BASF and Allianz. The 139 turbines have a total capacity of 1.5 GW and are seen generating fossil free electricity equalling the consumption of 1.5 million households.

To avoid stagnant water in the turbine foundation causing corrosion, water replenishment holes are typically used along with other measures.

“At Hollandse Kust Zuid, we optimised the holes to benefit marine life. By adjusting the size and the water depth at which the holes are placed, we created shelters for different marine species. Working with engineering departments, we ensured the water replenishment holes deliver on their technical purpose whilst providing a potential habitat for marine life," says Wilms who is working with the research project on Lillgrund as well as with the Hollandse Kust Zuid wind farm.

Larger rock protect cod and lobster

While all the rocks used for scour protections at the site can function as artificial reefs, specifically sized rocks were placed on the edges of the conventional protection around some turbines to create reef habitats that provide refuge to larger species, such as cod and lobsters.

The measures are being carefully monitored in collaboration with Dutch nature conservation organisation The Rich North Sea, Wageningen Marine Research and nature consultancy Waardenburg Ecology.

Apart from working towards the goal of a net-positive impact on biodiversity by 2030 for Vattenfall, there is also a financial business case for these measures, according to Wilms.

“The Dutch government is now including requirements for ecology and environment in the tender process – a growing and welcome trend in how countries handle offshore wind development,” he says.

“With this increasing focus on ecology and environment in today's tenders, we need to work towards building our knowledge on how to implement and test these measures. Therefore, learnings from research programmes at Hollandse Kust Zuid, Lillgrund and other offshore wind farms are important as these will ensure that we will also be strong and credible contenders in future bids.”

Subscribe to the newsletter THE EDIT

THE EDIT is Vattenfall's new monthly newsletter. Each issue highlights a new burning issue from the world of sustainable energy and fossil freedom.