Carbon capture, utilisation and storage sounds almost too good to be true. What role will it have in the transition to a fossil-free future? What are its advantages, and what are its drawbacks?

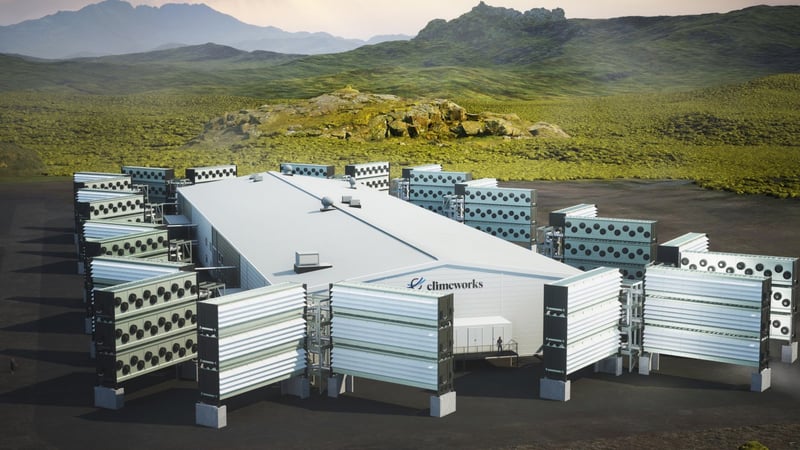

Climeworks direct air capture facility on Iceland. Copyright: Climeworks

With the climate crisis worsening, and transition challenges multiplying, all roads need to lead to – or at least towards – freedom from fossil fuels and reduced carbon dioxide emissions. Cutting emissions is currently the most obvious and most direct way forward. The electrification of transport, making electricity use more efficient, reducing dependence on fossil-fuelled heat, and increasing production and use of hydrogen in industrial applications are some of the necessary measures that are already being implemented.

“When you look at the carbon dioxide budget, it’s partly about halving emissions by 2030 and, by extension, reaching zero emissions by 2050 to avoid the worst effects of climate change. And the timeline gets tighter for every year that we delay. At the same time, there is cause for optimism as the cost of renewable electricity is falling, making Advswitching to renewables far more attractive,” says Amandine Denis-Ryan, CEO of the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) in Australia.

A potential way forward is carbon capture, usage and storage (CCUS). That is extracting carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and then either using or storing it. Ever since the first full scale direct air capture and storage plant started in Iceland in 2021, more and more projects have been developed. What impact the method will have remains unclear, according to Denis-Ryan.

“I think that emissions reductions will play a bigger role than carbon capture and storage. CCUS will probably have a role in some niche applications, but it’ll have quite a limited effect in terms of emissions reductions, so energy efficiency, electrification, and fuel shift are likely to do the heavy lifting,” Denis-Ryan says.

She further explains that CCUS currently presents a challenge due to its high investment costs for many companies and the fact that it has already been around for some time and has yet to deliver the results that many had hoped for.

However, the technology is still relatively new. For the past two years, researchers Placid Atongka Tchoffor, from Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, and Jan Suchorzewski, from Gdansk University of Technology in Poland, have been running one of Sweden’s first CCUS projects. The researchers are investigating the possibilities and challenges of using alkaline-rich residual materials from the mining industry to capture carbon dioxide where possible to use the carbonation products in various applications, such as building materials.

“CCUS is a broad term and the amount of investment required depends a lot on the technology used. In our project, we start with materials that contain magnesium and calcium, both of which can bind carbon dioxide. The method is called carbonation and can be used at normal temperatures and pressures. If rapid results is not a priority, passive carbonation can be used, which in principle does not require any energy, but the material is allowed to stand over months to years and binds carbon dioxide from the atmosphere,” Atongka Tchoffor explains.

The project is a collaboration between the Swedish Research Institutes, RISE, Chalmers University of Technology, and the University of Turku in Finland. Experiments in the project has shown that it is possible to create clean products from material created through carbonation. Atongka Tchoffor says that construction, paint and pulp industries are sectors where carbonation products can be particularly useful.

Denis-Ryan also believes that CCUS could be viable. At least at a smaller scale.

“In industry, it will be possible to electrify many processes or replace fossil fuels with green hydrogen, but I also believe that CCUS can play a small, but key role in areas where there are currently no renewable energy solutions, for example in the cement industry.”

Although Denis-Ryan and Atongka Tchoffor do not fully agree on the potential of CCUS, both believe that the technologies will be needed to meet the challenges of climate change in the most integrated way possible.

“We won’t achieve the climate goals without carbon capture and storage (CCS) and CCUS. We have oil production, metal production, lots of paper mills, and energy companies. What should we do with all the carbon dioxide they emit? Especially emissions from hard to abate industries? We need technologies to capture it, store it, or process it,” says Atongka Tchoffor. Meeting Sweden’s climate goal requires negative emissions of at least 11 million tonnes per year by 2045 – this clearly highlights the necessity of CCUS technologies such as direct air capture to meet this goal.

Is there enough space to store all the carbon?

“That’s not a big issue right now. There’s plenty of space to store carbon dioxide. The more pressing problem now is the lack of infrastructure needed to collect, transport and store carbon dioxide. That’s the challenge.” Atongka Tchoffor says.

This is CCUS

Carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) is a method where you capture CO2, often from large point sources like fossil fuel-driven industrial facilities and/or directly from the atmosphere. The CO2 can then be used on site or compressed, transported and stored in deep geological formations. CO2 can be utilised in production of methanol, polymers and as a feedstock in the production of carbon fiber and for many other applications.