Please note that this story is from 2017.

- None of the units at the Stenungsund plant are operational anymore.

- The oil-fired power plant would require extensive renovation and training of operating staff to be operational.

- The plant’s water treatment activities are still ongoing.

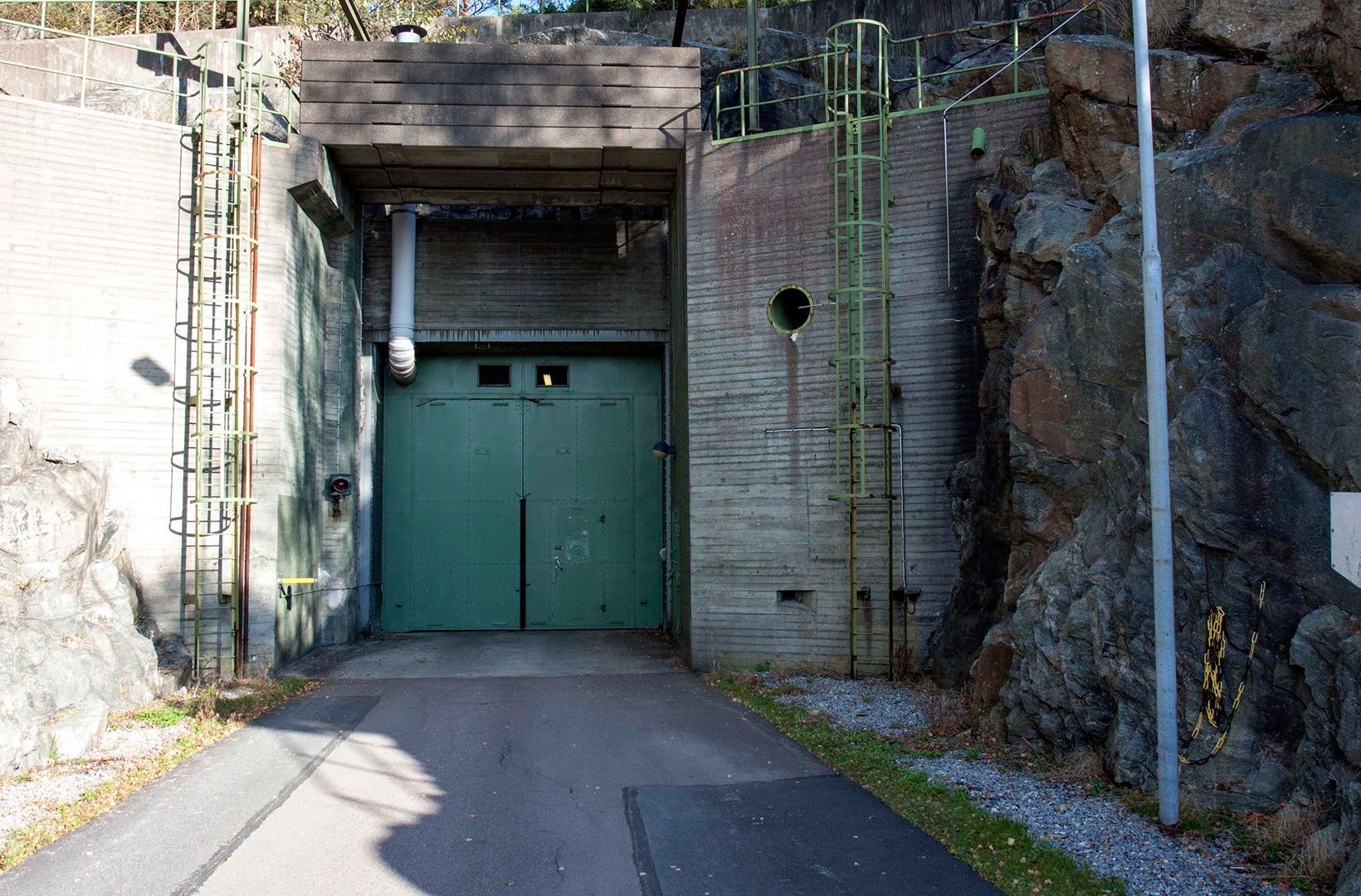

Gigantic steel doors in the mountain hide a cold war secret.

The fact that Stenungsund Power Station was built as a wartime safeguard is clear before you even enter the facility. Above all the entrances to the plant you see large blocks of concrete that could, in the event of attack, be used to barricade access, and the main entrance has a thick steel door allowing the plant to be isolated entirely from its surroundings. Luckily our guide, Thomas Wikström, Business Area Manager, Thermal Services in Vattenfall Services Nordic, has been entrusted with a passcode to let us in.

"If you look at the entrance tunnels, they are all curved as we wouldn't want anyone to be able to shoot directly into the machine hall," Wikström explains as we move through the gigantic tunnel into the mountain. "Inside, we have 600 caves of various sizes blasted in the mountain to make room for four fully equipped power plant units, a water treatment facility and huge oil storage caverns ensuring that the plant could be self-contained in case Sweden was attacked from the east."

Today, Wikström can reveal the story of the undercover plant without breaking any Swedish secrecy acts, but in the 1960s and 1970s when the Cold War was hot, it would probably have put him in jail for treason.

From seaside resort to war time power supplier

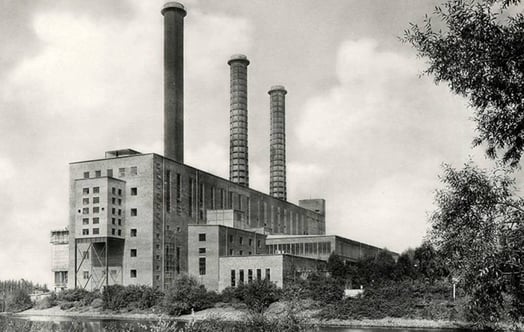

After World War II, the Swedish government started to look for the right location to build a protected power plant – in a mountain with a deep and ice-free harbour. They searched the entire Swedish west coast for a mountain that was large enough to hold big boilers, generators and equipment. The then small seaside holiday resort of Stenungsund turned out to meet all these requirements, and in 1956 the first detonations resounded in the otherwise peaceful archipelago in western Sweden. An impressive 1.5 million cubic metres – or three million tonnes – of rock were removed to make room for the power plant and its auxiliary systems.

Over the ten-year period from 1959 to 1969, four oil-fired power plant units were fitted into caverns to serve as peak and reserve load plants in peacetime and, most importantly, to be ready to supply electrical power to Sweden after a war, when all other plants and infrastructure had presumably been wiped out. The only giveaway of what is inside the mountain is four majestic chimneys protruding out of the top of the mountain. Should they be destroyed by bombs, the chimneys have been designed so that all the debris would fall into a deep hole inside the mountain, thus allowing the flue gas to continue flowing out and for the plant to still produce electricity.

2 x 260 MW units are still operational.

Up until the oil crisis in the 1970s, the plant actually ran as base-load much of the time. The two small 150 MW units were decommissioned in 2009, while the two 260 MW units are still operational.

No standard solutions

Inside the mountain, side tunnels and purpose-built caverns come like pearls on a string. Mobile phones do not work inside the mountain so the whole power plant has its own telephone system with personal alarm functions, because in the large and scattered plant, staff often work alone. 16 lifts in the mountain transport people and equipment from one level to another and a very complex fire alarm system has been installed since many caverns are unmanned most of the time.

A diverse modern business

Partway through the tunnel on the left hand side, through an inconspicuous side door, we find a complete water treatment facility. It draws water from a lake six kilometres away, converting it into nine million cubic metres of raw and process water for the plant, the surrounding industries and the municipality annually. Two of the nine million cubic metres of water provide fresh water for the entire Stenungsund municipality.

"Water is one of Vattenfall's four fields of activity in Stenungsund today. The peak load and reserve capacity power plant actually only accounts for 30 per cent of the business in Stenungsund, so over the years, commercial side activities have been developed including a harbour with port calls from more than 200 gas, oil and chemical tankers annually, to serve a large number of the local chemical industries; 520,000 cubic metres of oil storage located in 11 caverns, which we mostly rent out, and the water business that also sells raw, cooling and process water to external industries – all operated by -Vattenfall Services," Wikström explains. These activities help make the power plant profitable, even during long periods when the plant does not run. It also means that the plant can have a very slim organisation with high efficiency, as staff are moved between the different businesses based on need.

In the 1970s, when the four units were running 24 hours a day, Vattenfall had five full shifts of people - 330 employees in total in Stenungsund. Since 2003 the power plant has been part of the general Swedish power capacity reserve. In 2014 and 2017, however, the plant's two still active units did not win the power reserve auctions, which has led to an evaluation of various alternatives for the future of the plant. A final decision is expected during the second half of 2017.

Besides keeping the units in a limited state of readiness, the current 30 permanently employed staff are responsible and needed for running all activities in the harbour, the water treatment facility and oil storage, which brings a lot of synergies to the daily business.

![]()

Thomas Wikström

Age: 36

Job title: Business Area Manager and Harbour Master

Location: Stenungsund

Hobbies: Outdoor activities, orienteering and fishing, home projects, sailing

![]()

Ready to serve, if called upon

The mountain hides four fully equipped power plant units, two of which are still operational and ready to serve as a power reserve for the Swedish grid, if called upon.

![]()

Special signal system

Communication inside the mountain originally required a special light signal system, and even today a totally independent telephone system is in operation, as modern mobile phones have no reception inside the 600 caverns and widespread tunnels.

![]()

Electric moped

Electrician Kaisa Lithander runs her electric moped to cover the long distances between her different workplaces inside the mountain.